Arvo Pärt is one of those composers in the world, whose creative output has significantly changed the way we understand the nature of music. In 1976, he created a unique musical language called tintinnabuli, that has reached a vast audience of various listeners and that has defined his work right up to today. There is no compositional school that follows Pärt, nor does he teach, nevertheless, a large part of the contemporary music has been influenced by his tintinnabuli compositions.

Childhood and studies

Arvo Pärt was born on 11 September 1935 in Paide, where he also spent his first years. In 1938, the Pärt family moved to Rakvere, where he began to study piano at Rakvere Music School under Ille Martin. Having graduated from Rakvere Secondary School No 1 (1954), he continued studying music at the Tallinn Music School under Veljo Tormis. His studies were interrupted by mandatory military service in the Soviet Army (1954–1956), after which, in 1957, he continued at the Tallinn State Conservatoire under Heino Eller graduating in 1963. Several works composed during his student years still belong to the official list of his compositions: two sonatinas (1958–1959) and partita (1958) for piano, and orchestral works such as Nekrolog (1960), Perpetuum mobile (1963) and Symphony No. 1 (1963).

Early period (1958–1968)

Pärt worked as a sound engineer at the Estonian Radio from 1958 to 1967. Those were also the years of his early modernist compositions. Estonian music in the 1960s was shaped by an entire generation of innovative composers with a modern approach – although a few years older, besides Pärt there were Eino Tamberg, Veljo Tormis, Jaan Rääts and their junior follower Kuldar Sink. Almost simultaneously through their music all the most important styles and compositional techniques of the 20th century were introduced to Estonian music: neoclassicism, dodecaphony, serialism, sonorism, collage technique and aleatoricism. The works of Pärt proved to pioneer many of these areas: Nekrolog is the first dodecaphonic, Perpetuum mobile the first sonoristic and Collage über B-A-C-H (1964) the first work employing the collage-technique in Estonian music. Pärt had become one of the leading figures in the Soviet avant-garde. Nevertheless, none of those styles remained permanently in his work nor interested him for very long – many of his early compositions can be viewed rather as brilliant experiments or testing the boundaries. However, regardless of the chosen styles or techniques, Pärt’s early oeuvre is characterized by a punctual and powerful concept of dramaturgy, concentrated musical material and elaborated form – the elements, which are visibly present in his later tintinnabuli music and can therefore be characterized as the main pillars of his musical thinking.

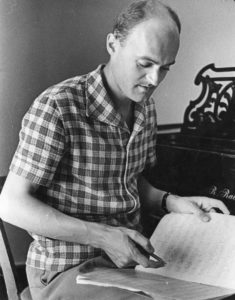

Arvo Pärt in 1962.

The most remarkable line of development in Pärt’s early compositions is his collages, which in his case are expressed in a personal and dramatic manner differing from the usual playful character of the collage technique. In his Collage über B-A-C-H, cello concerto Pro et contra (1966), Symphony No. 2 (1966) and Credo (1968), two musical but also spiritual worlds have been set against each other. He describes those worlds as if separated by a deep abyss, which, at the same time, he longs to transcend. Pärt’s dodecaphony here represents the “unbearable atmosphere of barbed wire” (to use his own words) of all modernist music, and the quest for beauty, purity and perfection is expressed through the stylization of Baroque music or concrete quotes primarily from Bach, but also Tchaikovsky, for example. Those works are witness to the growing inner anxiety and crisis for the composer. The most extreme and dramatic of them is Credo, composed in 1968 – it is the final renunciation of all means of expression used so far, the turning point in his oeuvre as well as his life.

The reception of his music in the Soviet Union at the time was conflicting and complicated. On one side, he was perceived as one of the most original and outstanding composers of his generation, whose works were also performed and acknowledged outside the USSR. On the other, many of his works composed in the 1960s were heavily criticized; for example, the neoclassical partita, but above all the dodecaphonic Nekrolog. However, it was not the composition style that caused the scandal following the premiere of Credo, but its inner message and choice of text as well as the “dangerously” strong impact it had on audiences (when the piece was performed for the very first time, the audience demanded a repetition). With its text in Latin “Credo in Iesum Christum” the composer openly and sincerely confessed to being religious, which was considered provocative and against the Soviet regime at the time. Credo was basically banned and Pärt, as well as his music, fell into disfavour for several years.

Paradoxically, Arvo Pärt was one of the most productive and highly valued composers for film in Estonia throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In 1967, he had become a freelance composer and after the events following Credo, film music was the only field Pärt could openly engage in. Pärt has composed music for many films – „Ukuaru“ (1973, directed by Leida Laius), „Diamonds for the Dictatorship of the Proletariat“ (1975, directed by Grigori Kromanov), „Navigator Pirx“ (1978, directed by Marek Piestrak), to name a few, and also music for animated films.

Years of crisis (1968–1976) and the birth of tintinnabuli

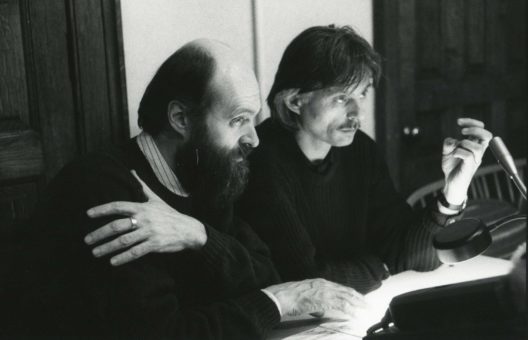

Arvo and Nora Pärt with pianist Helju Tauk (in the middle) at the rehearsal of Tabula rasa before the premiere concert, in 1977.

In Pärt’s creative biography, the years 1968–1976 mark his period of crisis – the final renunciation of the modernist techniques and means of expression used so far, searches for personal musical language and as a result, a radical change in the author’s style. “I didn’t know at the time that was I going to be able to compose at all in the future. Those years of study were no conscious break, but life and death agonising inner conflict. I had lost my inner compass and I didn’t know anymore, what an interval or a key meant,” Pärt recalled many years later.

In his new quest for self expression Pärt turned even more intensively towards the early music and became absorbed for years studying Gregorian chant, the Notre Dame School and Renaissance polyphony. The first signs of this appear in his Symphony No. 3 (1971) – one of the very few works that premiered in these years.

It was also the time of important events in Arvo Pärt’s personal life as he married and joined the Orthodox Church in 1972.

In 1976, Pärt emerged with a new and highly original musical language, which he called tintinnabuli (from tintinnabulum – Latin for ’little bell’). The new style first appears in a short piece for piano, Für Alina, followed soon by works like Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten (1977), Fratres (1977), Tabula rasa (1977) and Spiegel im Spiegel (1978). Pärt has now been composing in his tintinnabuli-style for over 40 years, and it has proven to be a rich and inexhaustible creative source.

Tintinnabuli music can be defined as a distinct technique, which in essence unites two monodic lines of structure – melody and triad – into one, inseparable ensemble. It creates an original duality of voices, the course and inner logic of which are defined by strict, even complicated mathematical formulas. Through that duality of voices Pärt has given a new meaning to the horizontal and vertical axis of music, and broadened our perception of tonal and modal music in its widest sense.

Tintinnabuli music can also be described as a style in which the musical material is extremely concentrated, reduced only to the most important, where the simple rhythm and often gradually progressing melodies and triadic tintinnabuli voices are integrated into the complicated art of polyphony, expressing the composer’s special relationship to silence.

In addition, tintinnabuli is also an ideology, a very personal and deeply sensed attitude to life for the composer, based on Christian values, religious practice and a quest for truth, beauty and purity.

After emigrating (1980 onwards)

The first tintinnabuli works were composed and premiered in Tallinn, Estonia – the USSR at that time. As did the avant-garde spirit of Pärt’s early works, so led the religious aspect of his tintinnabuli music to more and more controversial reviews and confrontations with Soviet officials. In January 1980, Arvo Pärt was forced to emigrate to Vienna with his wife Nora and two sons. A year later the family moved on a DAAD scholarship to Berlin, where they lived for almost 30 years.

As an active and productive composer, Pärt has continued composing since without any longer breaks. Vocal compositions, often based on liturgical texts or other Christian prayers, comprise a large part of his oeuvre. Among them there are many large-scale compositions for choir and orchestra, such as Passio (1982), Stabat Mater (1985), Te Deum (1985), Miserere (1989/1992), Berliner Messe (1990/2002), Litany (1994/1996), Kanon pokajanen (1997), Como cierva sedienta (1998/2002) and In principio (2003), as well as choral pieces with organ accompaniment or a cappella. One can say that the Word plays an important role in Pärt’s oeuvre because even many of his instrumental works are text related and the textural structure is often the basis of his compositional process (i.e. Psalom, 1985; Orient & Occident, 2000; Symphony No. 4, 2008 etc.).

It was also in Germany, where the lasting collaboration with Manfred Eicher, founder and producer of the renowned ECM Records, began. In 1984, ECM released Tabula rasa launching a whole new, highly successful series of recordings under the ECM New Series title, which brought Pärt to the world. His music was soon included in the programmes of many renowned festivals, orchestras and ensembles as well as television and radio broadcasts. Since this debut album, all the first recordings of Pärt’s major works have been released under ECM.

Back to Estonia

After Estonia regained its independence in 1991, the connections between the Pärt family and Estonia as well as its music scene were restored. In the 1990s, his works were often performed as part of Estonian concert programmes, and the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra and Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir under the baton of Tõnu Kaljuste also released their first recordings of Pärt’s music under ECM.

In the early 2000s, the tradition began of celebrating Arvo Pärt’s birthday with concerts in his childhood home towns of Paide and Rakvere, and also in Tallinn. Festivities on a grander scale have been organised in the composer’s jubilee years. At the initiative of the Estonian Music Days, the first exhaustive collection of conversations, essays and articles on Pärt was published in Estonian in 2005 (“Arvo Pärt in the Mirror”, compiled by Enzo Restagno), the radio show “Arvo Pärt 70”, consisting of 14 episodes by Immo Mihkelson was broadcast on Klassikaraadio (Classical Radio) and the international conference “The Cultural Roots of Arvo Pärt’s Music” was held at the Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre in 2010. Since 2010, Nargenfestival organises Pärt Days around the time of the composer’s birthday.

During the last decade, Pärt has rearranged approximately 30 of his earlier works as well as having composed around 10 new pieces, Silhouette. Hommage à Gustave Eiffel (commissioned by Orchestre de Paris in 2009/2010), Adam’s Lament (2010) commissioned for the European Capitals of Culture Istanbul 2010 and Tallinn 2011 premiering in Istanbul, Swansong (commissioned by the Mozarteum Foundation Salzburg and premiering at the Mozartwoche 2014), and Greater Antiphons (2015), commissioned by the Los Angeles Philharmonic and premiered by the same orchestra under the baton of Gustavo Dudamel.

Arvo Pärt has lived permanently in Estonia since 2010. The same year, on the initiative of Arvo and Nora Pärt, the Arvo Pärt Centre was established in Laulasmaa. In collaboration with the composer himself and his family, the APC aims to create and maintain the personal archive of the composer.