Karin Kopra, the Arvo Pärt Centre

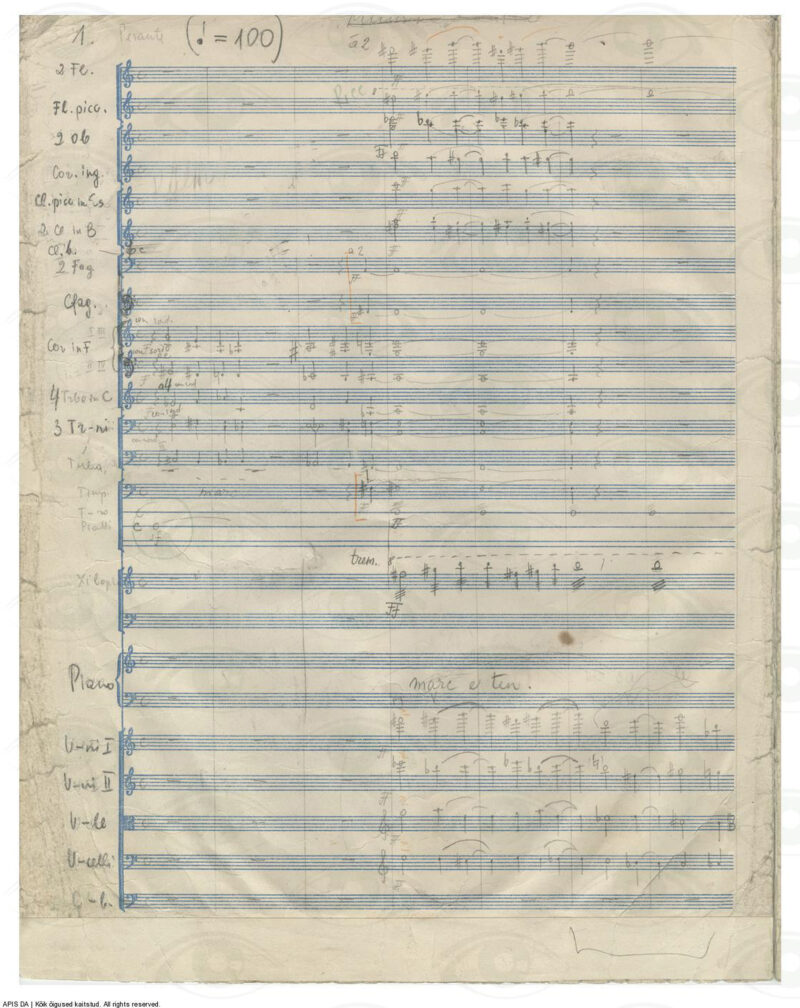

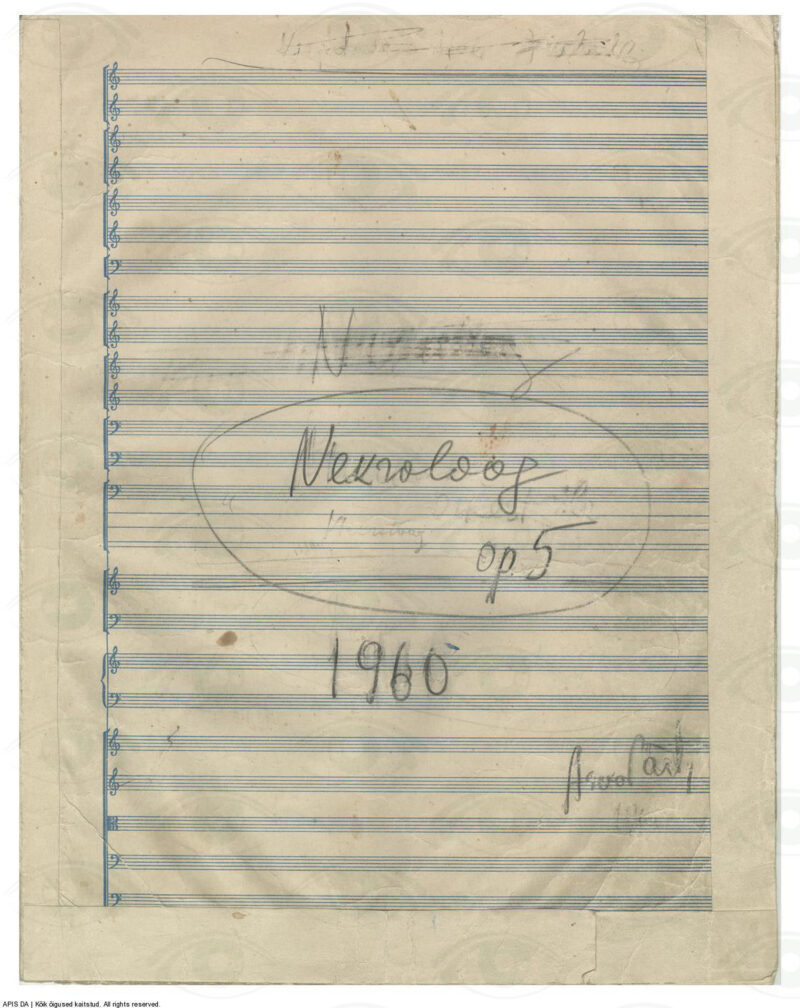

60 years ago today, on 11 March 1961, Arvo Pärt’s Nekrolog for orchestra was performed for the first time in the Pillar Hall at the House of the Unions in Moscow, under the baton of Roman Matsov.

The tumultuous story of Nekrolog proves the extent to which the reception and fate of a composition depends on the time and the place the work was written, and the impact a work can have on a composer’s entire future oeuvre.

During a discussion on creative history of the work held on February 16, 2021 at the Arvo Pärt Centre, Arvo and Nora Pärt reminisced about that time long ago when the composer wrote his very first pieces: piano sonatinas, Partita, the cantata Our Garden and Nekrolog.

When Arvo Pärt, a 25-year-old student of the Tallinn Conservatory, brought his first symphonic composition to the weekly listening meeting of the Estonian Composers’ Union on 4 October 1960, it resulted in a discussion on musical aesthetics and ideology that almost escalated into a pan-Soviet scandal. Namely, this was the first time in Estonian music history when dodecaphony was used, which is a composition technique based on the equal use of the 12 chromatic notes, and tone rows or series comprising these notes. Although dodecaphony had been known in Western Europe for almost half a century, the members of the ECU committee were confused: does a composition technique invented in the West even have a place in Soviet music? And what is more: what means of expression and techniques are even allowed in contemporary art, so that they would not diminish the value of the work and alienate the audience?

Before composing this work, Arvo Pärt independently studied the dodecaphony textbooks written by Ernst Křenek and Herbert Eimert, which had reached his teacher, Heino Eller, from Eduard Tubin in Sweden. Spurred by curiosity, the young composer immediately tested the textbook knowledge in a symphonic score, without much thought for possible consequences.

The tense dissonance-rich sound of Nekrolog, representative of the avant-garde of the 1960s, is like another world compared to what we now recognise as Pärt’s sound. And yet, already during the first listen of the work, its masterful orchestration, intense dramaturgy, spiritual concentration and characteristic musical images were noticed.

Why or to whom did such a young composer write an obituary? At that time, it would have been impossible to explain the rationale behind the work: it is a necrologue for the living rather than for the dead, an obituary for the entire degenerate world with all its suffering. In order to be able to record and perform the work in public, the pseudo-dedication “In Memory of the Fallen of the Fascist Concentration Camp at Kalevi-Liiva” was given to the work on the recommendation of friends. This dedication was also intended to justify the tragic sound of the composition, which did not at all fit in with the main requirement of Soviet music, “socialist in content, but national in form”.

Despite the allusion to the victims of fascism and the fact that the work was performed in Moscow under the neutral title Music for Orchestra which obscured the actual content, Moscow apparatchiks remained suspicious. “If a young composer expresses spiritual defeat, injustice and tragic helplessness in his music, why is there no indication in the work that our people won?” a renowned Soviet critic wrote in the journal Sovetskaja Muzyka after the premier of Nekrolog. “He could have tried to find what should actually be expressed in a work of art: the strength of the human spirit, resilience, faith in progress.” (Juri Korev, “Po povodu odnogo kontserta”, Sovetskaya Muzyka, 05.1961, pp. 131–132).

At the plenum of the Union of Soviet Composers the following year, the work was labelled “avant-garde bourgeois music”. Strangely, the work was nevertheless performed in Leningrad in May 1962, and then also in Geneva and Zagreb, before it was buried for years.

When Arvo Pärt became a member of the Estonian Composers’ Union on 9 September 1961, Nekrolog was not on his list of works.

The first performance of Nekrolog in Estonia took place only in 1966, by the Estonian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Eri Klas. But a few years later, in 1969, Nekrolog was paradoxically submitted to a competition of patriotic compositions of the Soviet Union. Moreover, by 1970, the twelve-tone technique had been explored by many Soviet composers, including Tikhon Khrennikov, the Secretary of the Union of Soviet Composers, who had voiced the strongest accusations of formalism and a lack of principles.

Arvo Pärt was not in the least perturbed by the confusion around Nekrolog, and developed his dodecaphonic skills in quite a few compositions that followed: Perpetuum mobile (which received a lot of recognition and was widely performed), Symphony No. 1, Diagramme, and others, including Credo.

In retrospect, we can say that Nekrolog became “ground zero” in Arvo Pärt’s oeuvre, beginning the basis of the composer’s deep spiritual and musical explorations, culminating in the invention of his own sound in 1976: tintinnabuli.

Today, Arvo Pärt’s early works live their own lives, independent of any political ideology. But even now, 60 years later, musicologists are debating his approach to dodecaphony, and the composer himself has made small additions to the score, most recently to help with the recording made by the Brno Philharmonic and conductor Dennis Russell Davies on 9 February 2021.