Text by Karin Rõngelep

Writing a cantata for children was a natural step in Arvo Pärt’s creative path, as the young composer had considerable contact with children. For example, in 1956–59, he worked as a piano accompanist and musical director with the Tallinn Pioneers’ Palace drama club, improvising background music for plays and writing children’s songs. A children’s choir, founded in 1951 by Heino Kaljuste, was also rehearsing at the Pioneers’ Palace on Aia Street around that time and had already reached a remarkable level under the ambitious young conductor. Heino Kaljuste might have run into Arvo Pärt in the building one day and suggested that the composer write a children’s cantata. Having gotten verbal consent from the composer, Kaljuste might have gone to an official of the Union of Composers. What happened next has been documented in the archive.

28 May 1959. Application to the Union of Soviet Composers for a contract to write a new composition. Signed by B. K., or Boris Kõrver, who asks the Moscow authorities for permission to write a work-themed cantata for the pioneers’ choir, composed by a student, Arvo Pärt. What could Moscow have against that? 8 June 1959 The Union of Soviet Composers permits “Comrade” Pärt to sign a contract with the Musical Foundation of the USSR to write a cantata.

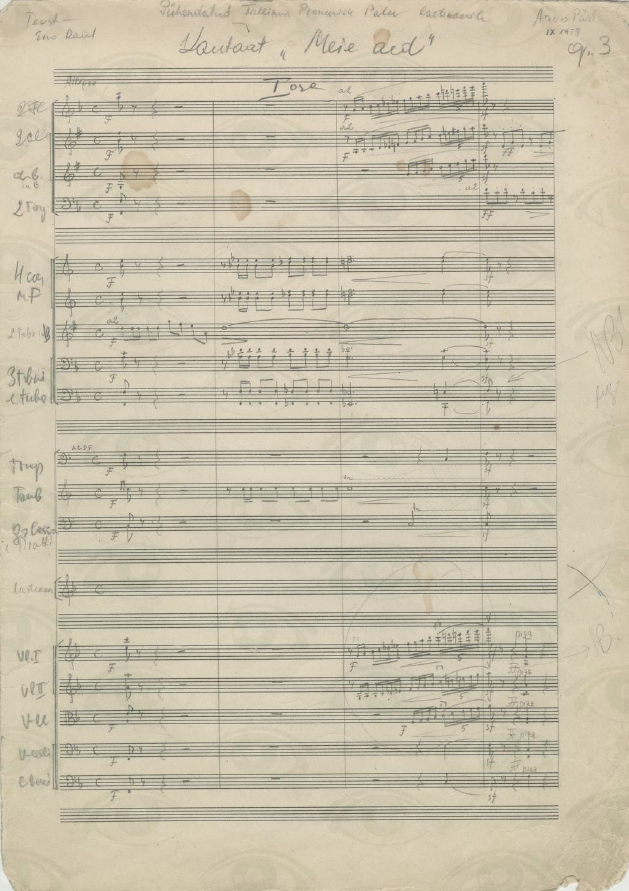

Once permission was received, the work took no time at all in the hands of the young composer, who, at the same time, was completing a course at the conservatory and working for Estonian Radio and the Pioneers’ Palace. The first nearly completed handwritten score is dated September 1959.

The text of the cantata comes from the beloved children’s author Eno Raud, whose daughter Piret Raud recalls: “I remember from my mum’s stories that my dad and Arvo Pärt were good acquaintances at the time, who moved in the same circles, and that Arvo Pärt commissioned the text from my father. Through it all, they didn’t hold back their inner smile, so to speak. The humour in the text is, in any case, very typical of Eno Raud, and I have wondered whether people today who are not familiar with the context will even notice it. This is a text written with great relish for a good acquaintance!”

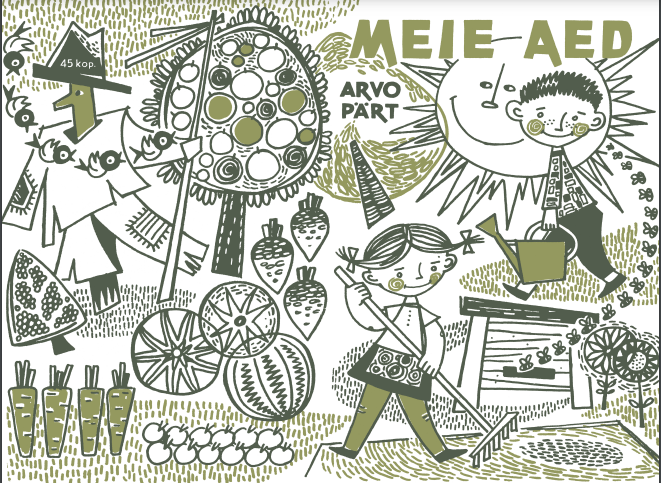

Eno Raud’s text is indeed witty. On the one hand, it seems to fit with the Moscow mentality, inviting children to work for the joy of the homeland. But on the other hand, it contains no pioneers, no great homeland, and no other references to symbols of communist ideology. The text is topical at any time, especially nowadays, when having a green thumb is particularly trendy.

If Pärt’s work from the late 1970s onwards can be considered “music born of words”, then in its own way, the text of Our Garden is also the greatest source of inspiration for the music. The music of Our Garden is a colourful, evocative illustration of activities in a garden, at times bubbling with children’s energy while at other times sun-weary. Even without the lyrics, the music tells the same story of children’s activities at a school’s test garden.

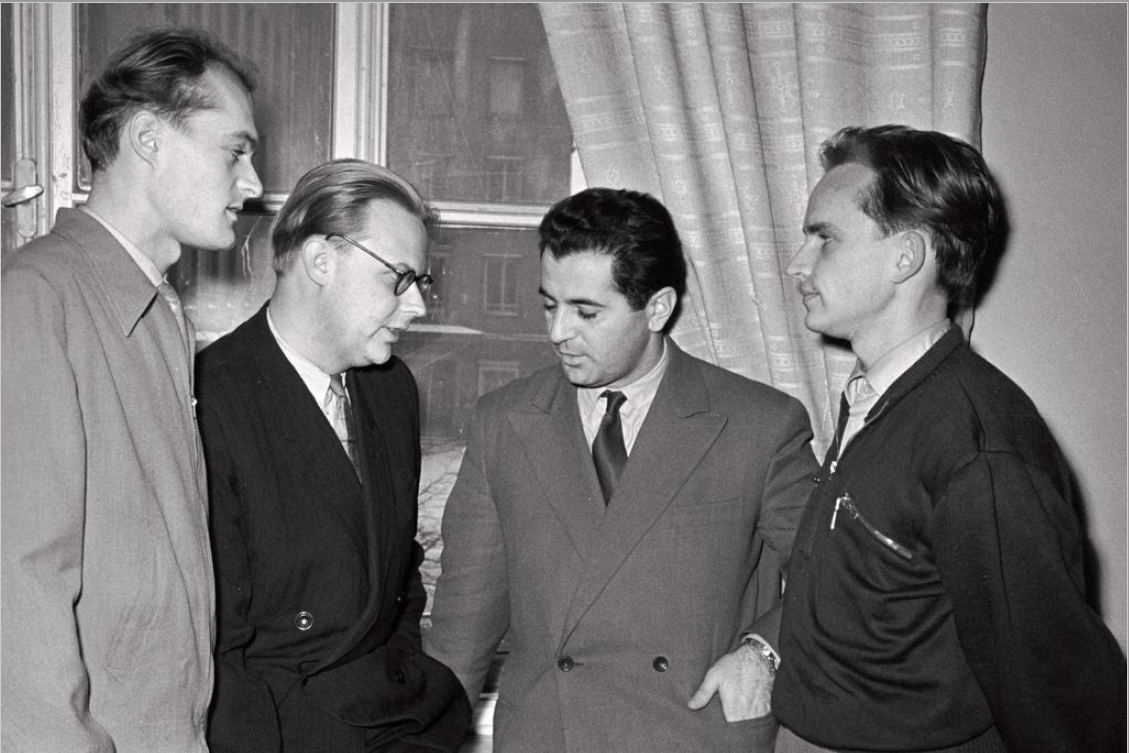

The archive of the Arvo Pärt Centre contains a photograph of the young composers Arvo Pärt, Eino Tamberg, Edgar Oganesjan (from Armenia), and Jaan Rääts posing for the camera. This snapshot dates from a December day in the Estonia Concert Hall in 1959, when a creative meeting of Armenian and Estonian composers took place. Our Garden was premiered there by the Children’s Choir of Tallinn Pioneers’ Palace and the Estonian Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Roman Matsov. Ofelia Tuisk’s programme includes notes saying that Arvo Pärt is a second-year student who is currently working on a concerto for two pianos and orchestra (which for some reason was never completed) and that Pärt has already composed music for five children’s plays.

Young composers (from left) Arvo Pärt, Eino Tamberg, Edgar Oganesyan and Jaan Rääts at a creative meeting of Armenian and Estonian composers on 25 December 1959 at the Estonia Concert Hall. Photo by O. Tuulik

Six months after the work’s premiere, at the spring concert of the Children’s Choir of Tallinn Pioneers’ Palace (later Ellerhein), the choir was accompanied by the energetic young composer-pianist himself on the piano.

The archive recording comes from the archive of the Estonian Public Broadcasting.

Our Garden is a kind of mixture of children’s music and experiments with different styles, which Pärt loved to do in his youth. It has a particular kind of zest, immediacy, and positivity. Other works from the same period are much more serious and intense, lacking the same pure spontaneous joy.

The work is structured like a mini-symphony, consisting of four contrasting movements. The orchestration is astonishingly masterful for a 23-year-old composer. Nor is there a lack of a dramatic composition – the music unfolds a complete story with its own twists, turns, humorous moments, and climax. Listeners are delighted by bright themes, such as the theme of the bumblebee or the scarecrow, the barcarolle in the second part reminiscent of a scene from Tchaikovsky’s “The Nutcracker”, or the march-like character of the overture, which on the one hand fits Soviet tastes but on the other does not lack some trickery – its alternating meter. Just try to march to an alternating meter…. In the section about the war against the thistles, there is also a real fight in the orchestral part, a tense dramatic development. Harmonically, this music is as colourful as the world of a child. The composer enriches the music by juxtaposing distant keys and even employs polyphony, which could be considered a musical representation of weeds.

And yet there is already something in this work, which Pärt created at a very young age, that connects his early work with his utterly different tintinnabuli-style work. First is the structure of the work – a strict and clear structure is characteristic of Pärt’s entire oeuvre. Second is the economical handling of musical material. There’s nothing superfluous about the music, and the proportions are just right, making it accessible to listeners of all ages.

At the age of 27, Arvo Pärt received the first major accolade of his life – first prize in the 1962 Union-Wide Composers’ Competition. The prize was for two works: the children’s cantata Our Garden and the oratorio Stride of the World. This was a remarkable achievement, as dozens of composers under the age of 33 took part in the Estonian preliminary round alone. One can only imagine how many young composers took part from all over the Soviet Union. Only a few years earlier, the general secretary of the Union of Soviet Composers, Tihhon Khrennikov, had sharply criticised Pärt’s first orchestral work, Nekrolog, as an example of “formal experimentalism”. Scathing criticism on the one hand and the greatest accolade on the other: this demonstrates very well how difficult life was for young creatives in 1960s Estonia.

Heino Kaljuste, the initiator of youth song festivals, took Our Garden to the 1967 youth song festival, as featured in the documentary film Rainbow, which can be found in the ERR archive. Given the technical complexity of the work, it must have been a big gamble.

Immediately after the completion of the work, the cantata was translated into Russian (by T. Sikorskaya). In 2003, an English translation was done by Maarja Kangro. It’s nice to know that in English, Our Garden has delighted audiences in concert halls in Sweden, England, Spain, Italy, and Monaco. In 2025, it is due to be performed at the prestigious Gewandhaus in Leipzig. A score for a new arrangement for a children’s choir and chamber ensemble is in preparation, which will allow for more frequent performances of the work.

Our Garden is the symbolic starting point in many ways. It is the first work in Arvo Pärt’s extensive choral oeuvre, which is a quintessential reflection of his creative genius. It also shows Pärt’s playful side, which becomes much more restrained in his later works.

Summer is coming, “That’s enough, we have to stop it, Soldiers, do you hear the whistles? Take your hoe and do not drop it: Let’s declare now war to thistles!” [1]

[1] Lyrics of “Our Garden” by Eno Raud; English translation by Maarja Kangro.

Read more about the piece: https://www.arvopart.ee/en/arvo-part/work/594/