Maarja Tyler, Arvo Pärt Centre

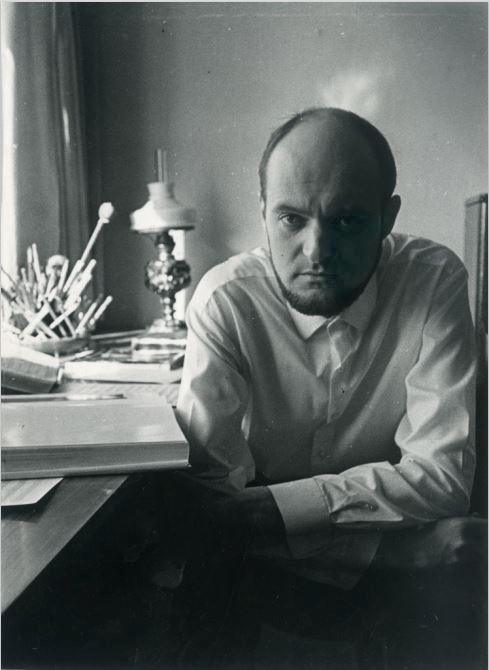

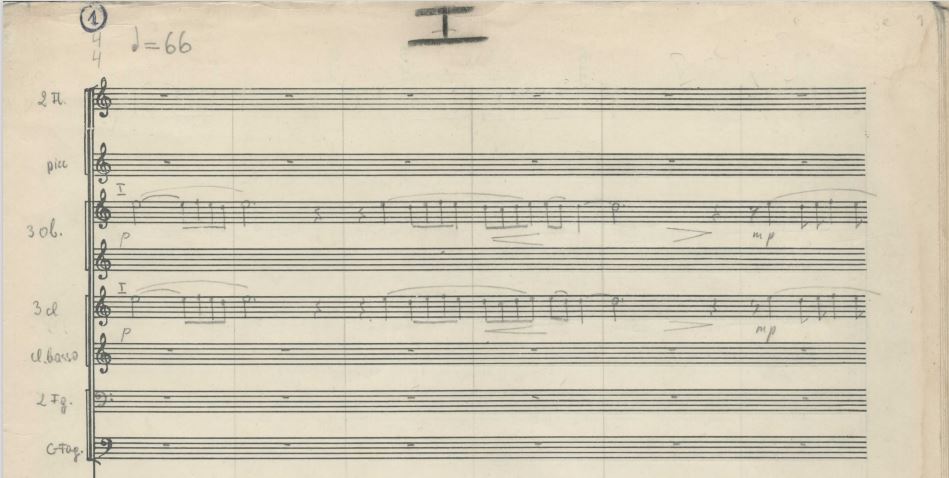

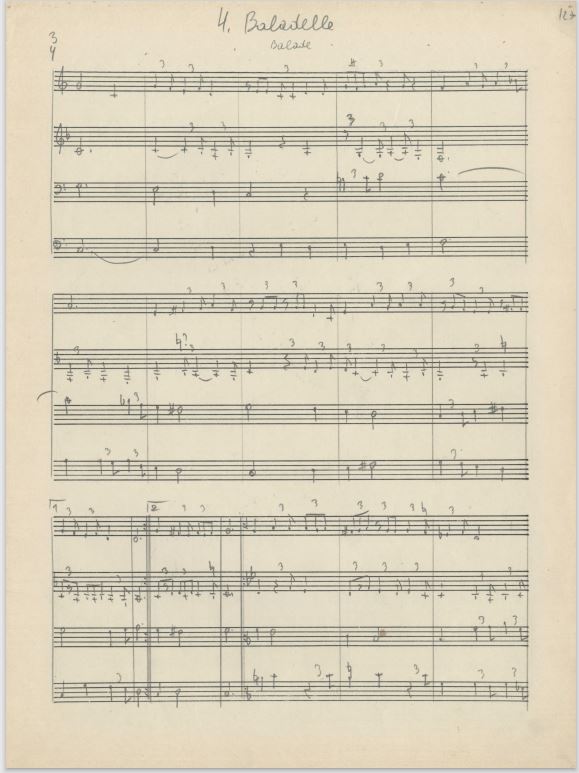

This time, Arvo Pärts Symphony No. 3 was the focus of the conversation, based on archive materials. Written for a large orchestra in 1971, this voluminous work is the only concert piece created during the transition period that is part of the composer’s official list of works.

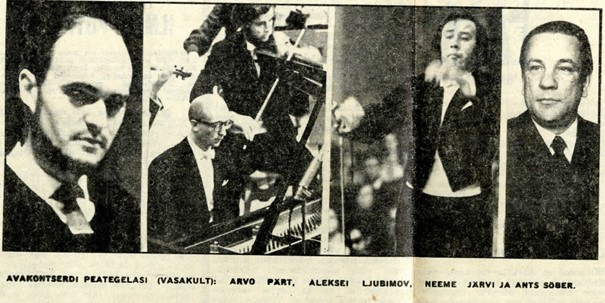

The premiere of the symphony took place at the Estonia Concert Hall in September 1972 with the Estonian Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Neeme Järvi. It was a much-anticipated event, especially since four years had passed since the completion of the last work, Credo, of the otherwise prolific composer. Few people knew that Arvo Pärt’s inner conflict of values, which had beset him for years, culminated in 1968, when he decided to finally abandon the dodecaphony and modernist sound aesthetics that had exhausted him. This radical renunciation brought with it a certain liberation, but also a fundamental consequence: the question of how and with what to fill the creative vacuum that had suddenly appeared.

While Pärt had occasionally linked his music to the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, he now turned his gaze even further back in the history of music. Pärt has recalled that an important moment during the period of his search was the first encounter with Gregorian chants. Pärt recalls that it happened at the end of the 1960s in a bookstore on Harju street, when suddenly a Latin chorale came over the speakers. The fleeting yet indelible experience left a deep imprint on the composer’s consciousness. The realisation that the key to music lay in unison kept Pärt seated at the piano for days, where he played prayer melodies from the collection Liber usualis. In retrospect, he has compared the process of learning Gregorian chants to a blood transfusion. It was especially important for the composer to understand the secret of songful melody and to realise that each phrase could breathe: “For me, this change meant that I began to look at each musical movement, each phrase, from a different perspective.” [1] The influences of medieval music and vocal thinking can be heard in the cantilena-style melodies of Symphony No. 3, especially in the meandering opening theme, which moves step by step around the main pitch.

During the creation of Symphony No. 3, Pärt studied not only medieval music but also Renaissance polyphony. Through friends who had given concerts abroad, he obtained recordings of early music. Together with the like-minded composer Kuldar Sink, Pärt studied foreign-language books that explained the spiritual background and performance context of historical musical heritage. During his visit to Moscow in 1970, Arvo Pärt had the opportunity to explore music libraries, and it is highly likely that two of his manuscript transcriptions, Jacob Obrecht’s Missa Maria zart and a collection of works by Guillaume de Machaut, which can be found in the Centre’s archive, originate from that period.

The detailed transcription of these musical works allowed him to understand the music from the inside. In addition to studying technical compositional aspects, Arvo Pärt also perceived the spiritual values behind the strict rules of early polyphony: “I have defined the strict style for myself as кротость и смирение (i.e. ‘gentleness and meekness’): it is a narrow path. It is like a school of soul and spirit, a system of virtues that keeps you from falling at every step. It is treating each sound with love: to seek that love between two sounds, and three and four and …”

Arvo Pärt’s musical quest found artistic expression in Symphony No. 3, which was completed at the same time. Although it is easy to find similarities with the intonations and counterpoint techniques of 14th- and 15th-century choral music, the symphony lacks direct quotations. During our conversation, it became clear that, when creating this piece, the composer seemed to be returning to the basics of music writing. He was trying to write a narrative, an evocative and gripping large-scale work that grew out of a single musical cell. Nora Pärt added an interesting comment about the importance of Symphony No. 3 for the rediscovery of creative spontaneity: “It is perhaps the first work in which Arvo tried to let himself go and consciously turn off earlier structures, because he thought that this skill had dried up with the dodecaphony. So all these sounds and shapes grew out of purely musical perception and thinking, and that was the goal.”

Diving from modern times into such a distant past, trying to understand the thoughts and creative work of the people who lived at that time, the dignity and beauty they exuded, was a source of great joy and inspiration for the composer. During our conversation, Arvo Pärt recalled his state of mind when writing this work: “I really had a feeling of liberation, of things falling away. I feel like I was very happy at the time, writing it. It was like going to the other side.”

Concert reviews published after the premiere of the symphony point out the mystical atmosphere and asceticism of the work. They also try to analyse the reasons behind Pärt’s stylistic changes and predict what direction the composer might take. Music critic Merike Vaitmaa, however, questions the value of conjecture and argues that the impact of Pärt’s works does not depend on the style chosen: “I’ve heard all sorts of predictions and declarations, such as ‘He won’t write like this for long’, ‘He should continue in this direction’ or ‘He should now combine his different styles’ …. I must admit that when I try to comment on such opinions, I feel my incompetence as a critic very keenly. Therefore, as a listener, I will say that I find Symphony No. 3 to be beautiful and profound music /…/ and I look forward with interest to his next works, not knowing exactly what they will be.”

Hardly anyone, including the composer himself, could have imagined at the time that Symphony No. 3 was just an islet in the middle of the open sea and that it would take another four long years to discover his new musical language: tintinnabuli…

[1] Jõks, Eerik (2010). Contemporary understanding of Gregorian chant — conceptualisation and practice. PhD thesis. University of York, Faculty of Music.